Burning Buses and Rioting Teenagers – the Northern Ireland Conflict in the Age of Brexit

Sectarian violence in Northern Ireland was largely thought to be something of the past, albeit the fairly recent past, until pictures of burning buses and rioting teenagers made their way around the world about two months ago. Read on to find out why the conflict has resurfaced, why now, and what it might mean for the future of the United Kingdom. By Annette Steyn

Last time I was in Northern Ireland, during Belfast Pride 2018, it struck me as, by and large, a post-conflict society. I was doing an internship at a local LGBT organisation – helping out at inclusivity workshops for the civil service, panel discussions with the Police Service of Northern Ireland and the information booth at the Pride Parade. Sauntering up and down Belfast on my days off and on the drives to and from events, workshops, etc., which became somewhat of my own personal whistle-stop tour, I grew absolutely fascinated with the city, the country and its past. The recent history of violence and the unresolved issues that plagued its political landscape and the day-to-day of its people had left notable marks all over Belfast and hung palpably in the air.

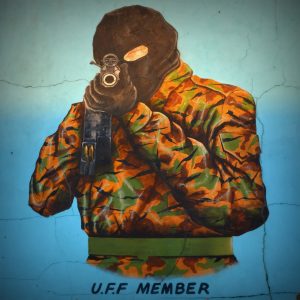

Protestant communities were marked with the excessive display of the Union Jack – hundreds of small flags strung between lampposts, hectically jittering in the wind or murals glorifying the flag across red brick walls. However, the Catholic communities marked their territory with bilingual street signs, pub and shop names rather than forcing the Irish flag up every lamp post and onto every wall. The flair was distinctly Irish. (I will refrain from being sappy and pointing out that the only flag I spotted in both Catholic and Protestant communities was the Pride Flag.) On one particular drive back from a workshop at Stormont Castle, my mentor took me on quite a morbid sightseeing tour: places where the most seminal scenes of ‘The Troubles’ had played out. “Do you see that fence up there?“ He was referring to a monstrosity of a barbed-wire fence one could easily mistake for the border in Melilla, stretching at least 4 meters into the grey sky. “That’s a peace line. Just on the other side of it is a Catholic area”. He explained that Catholic and Protestant areas were separated by such peace walls to protect both sides from sectarian violence. Calling such a construction a “peace line” seemed horrifyingly Orwellian.

Nonetheless, I, in hindsight quite naively, underappreciated just how close to the surface the sectarian conflict and, especially, its threat of violence was still lurking. Then again, I couldn’t have seen the extenuating circumstances of the COVID pandemic and Boris’ Brexit deal coming.

The History of the Conflict

To properly contextualise the recent outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland one must first recapitulate the history of the conflict. What follows can only be – at best – a gross over-simplification, seeing as the Irish conflict is centuries old, multidimensional and deeply personal to the people of Northern Ireland (of whom I am not one).

The origins of the conflict between majority Catholic Irish republicans and majority Protestant unionists lie as far back as the 12th century when the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland was to become the first of many British colonial endeavours. For centuries to follow, Ireland was governed by the English: English colonialists displaced Irish landowners and all but relegated the natives to subservient tenants.

Political and religious conflicts between the British and the colonized Irish persisted, culminating in the Irish war of independence of 1920-1921 that created the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland as a devolved government that was to remain part of the United Kingdom. The Irish, however, resented the arbitrary division of their country, and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland felt increasingly discriminated against as second-class citizens: The Protestant majority meant that political power, by default, lay with the unionists; the police force was overwhelmingly Protestant (and often hostile towards Irish nationalists) and many privileges were bestowed upon Protestant citizens by virtue of their cultural identity and – to some extent – their religious beliefs. Although the labels Catholic and Protestant are often used to describe the two sides (as I have done here as well), the conflict is, at its core, not a religious one but one of cultural identity – and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland felt their cultural identity and their rights were being stifled by a staunch loyalist majority.

Inspired by the surge of human rights movements in the 1960s, activists started protesting and demanding equal rights and treatment for the Irish minority living in Northern Ireland. One such protest in Derry in 1968, that escalated and was met with brutal and excessive force from the police, became the catalyst for what would come to be known as ‘The Troubles’ – a period of violent sectarian conflict between the paramilitary forces of the Irish nationalists and the loyalists and the British Army that lasted 3 decades and cost more than 3000 lives. The Good Friday Agreement, which was signed in April of 1998, is largely considered the official end of ‘The Troubles’. It codified into law a power-sharing system in the Northern Irish parliament, lay the groundwork for cooperation between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and clarified issues of sovereignty, security and civil rights.

The Re-emergence of Violent Sectarianism

Many – including myself – had believed, if not the conflict, then at least the violence that accompanied it to have (largely) been laid to rest in the late 90s. However, at the end of March 2021 said sectarian violence re-emerged on a scale not seen since the Good Friday Agreement: loyalist riots and violent clashes with the police took place in Derry and Belfast before the violence inevitably turned towards nationalists. The aforementioned peace walls became the epicentres of the conflict as rioters on both sides – overwhelmingly young teenagers – started throwing petrol bombs and rocks, setting the gates on fire and forcing their way into the opposite communities.

Political analysts see the recent resurgence of sectarian violence from unionists as a reaction to the fear of losing their British identity and the perceived gradual loss of the economic and political primacy Protestants once had over Catholics – with two recent developments aggravating these feelings:

In midst of the pandemic, a large funeral was held for a former IRA (Irish Republican Army) commander, Bobby Storey, with about 2000 attendees including high-ranking members of the Irish nationalist party Sinn Féin – members of the same government that were imploring citizens to limit the number of people at funerals to no more than 30. Even though it represented a massive breach of the COVID restrictions, no arrests were made and no one in attendance was prosecuted. This infuriated unionists who were increasingly starting to believe the police were siding with Sinn Féin and Irish nationalism.

In addition, the Brexit deal strained the situation in Northern Ireland even more:

In order to, as Johnson’s slogan so derisively read- “Get Brexit Done”, Boris and his government altered the EU Brexit deal to create a customs border along the Irish sea between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. This, of course, prevented a hard border between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland (which remains a member of the European Union). However, unionists felt they were being disregarded by the British government and were being separated from the union they so faithfully cling to. This recent surge in sectarian violence has not only proven the extent to which the conflict still looms over Northern Ireland. It has also created a lot of uncertainty around the future of Northern Ireland and has reiterated just how much of a threat Brexit is to the union: nationalist parties in Scotland, Northern Ireland and increasingly Wales as well are adamant about leaving the United Kingdom to govern without interference or oversight from Westminster.

Either way – whether Northern Ireland reunites with Ireland or not; whether the customs border is in the Irish sea or across Ireland – the conflict remains unresolved and the situation remains unsustainable and fraught with peril.